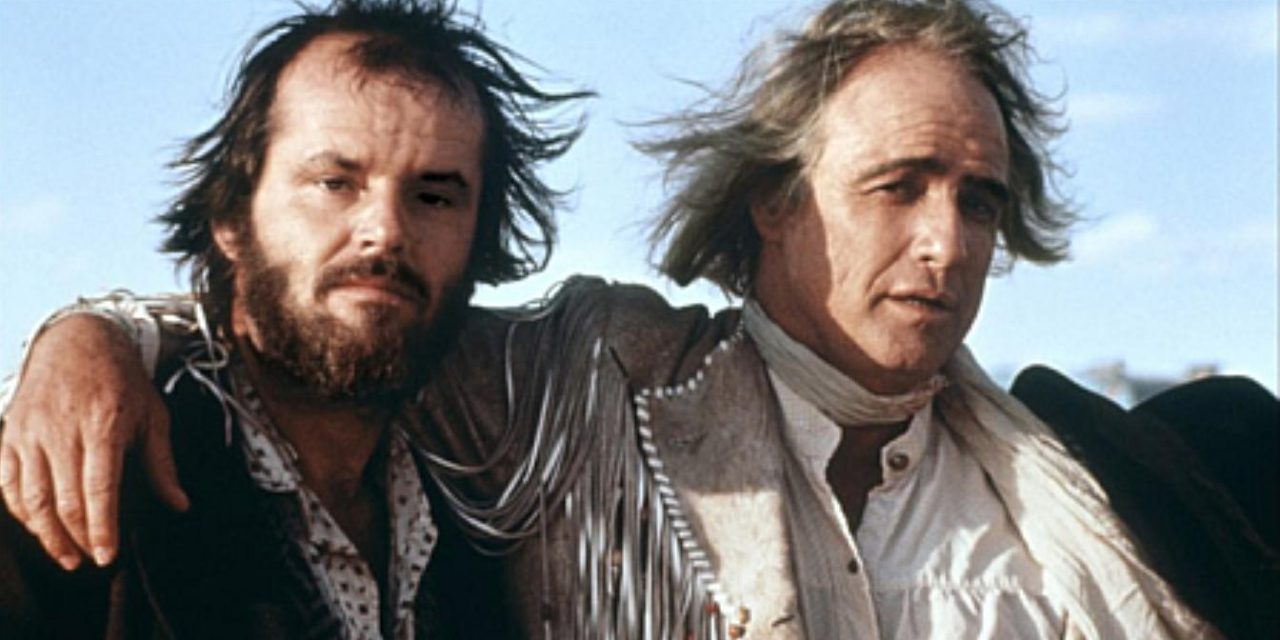

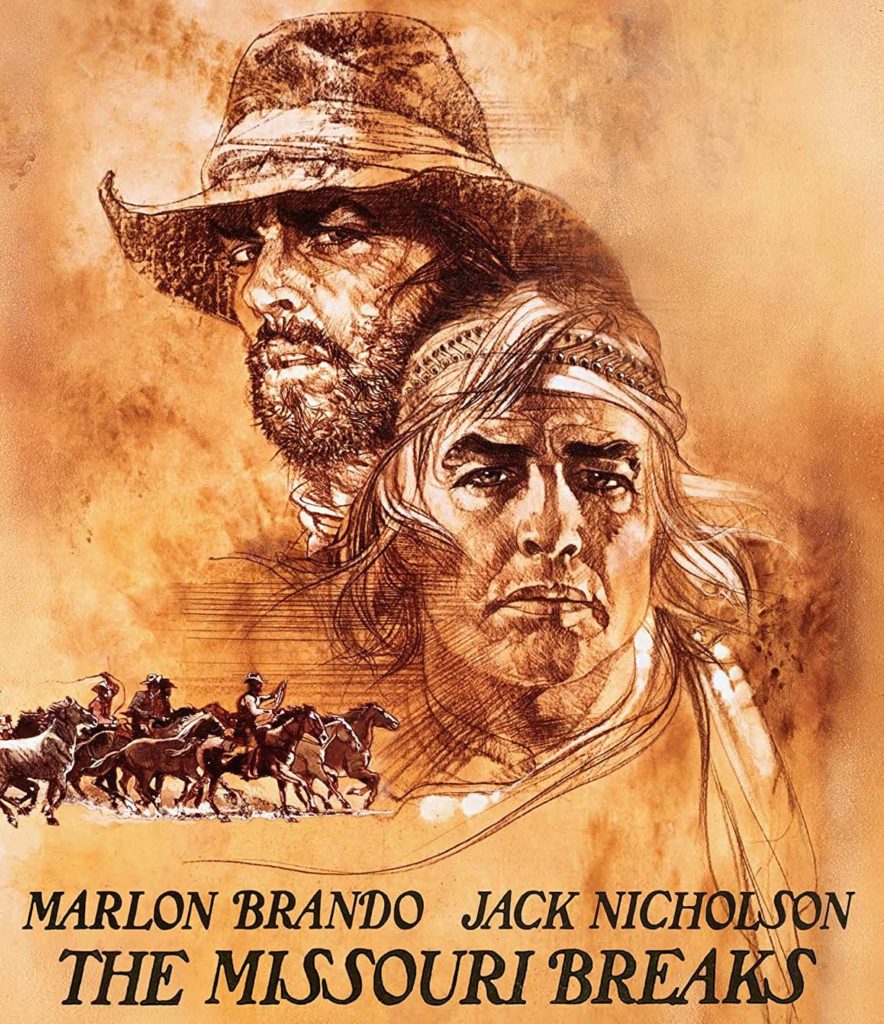

Howdy folks, Francis here again. Today I want to talk about a great Western film I’m betting you haven’t seen, or if you have, you likely forgot about it. It’s an underappreciated gem made at the very tail end of the dominance of the traditional western, and conforms to very little of the genre’s expected conventions. The movie is 1976’s The Missouri Breaks, starring Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando.

I recently rewatched this often forgotten classic, thanks to the great Pluto TV, which I know Martin is a huge fan of as well. Seeing it so far distant from the time it was made gave me some serious perspective on what it was attempting to do, and I feel it received a short shrift at the time and deserves an appreciative reevaluation.

The damn thing is excellent, and with performance powerhouses like Nicholson and Brando, it certainly should have been. Both of them were fresh off of their Best Actor Oscar wins, Nicholson for One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest in 1975 and Brando for The Godfather in 1972.

My theory on why this movie is not more revered is that it came at a strange time for the Western genre and it decided to subvert too many of its expectations. Clint Eastwood’s masterpiece The Outlaw Josey Wales was released barely a month later, along with John Wayne’s final movie, The Shootist, two months after that. Those two movies along with this one effectively brought the curtain down on the traditional Western forever. All those that came after 1976 were essentially a different breed entirely.

This movie has more in common with Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven sixteen years in the future than with any other western made at the time, which to me has only allowed it to age all the better. (They have similar themes and Unforgiven won Best Picture that year.) Had this movie been made even a decade later, the response to it would have been different I believe.

The movie takes place in northern Montana actually, the title is a reference to the Missouri River there and how rustlers would cross it. It occurs in an indeterminate Post-Civil War period, and is about a small time cattle rustling operation, loosely headed by Nicholson, which runs afoul of the local ‘cattle baron’ David Braxton, played capably by John McLiam. Braxton ends up hiring legendary ‘regulator’ Robert Lee Clayton, played with wonderful elan and not a little bit of glee by Brando, to essentially kill all of the local rustlers by whatever means he can.

Nicholson is able to camouflage himself and his operation by purchasing a local farm thanks to some ill-gotten train heist money that he and his gang (barely) manage to pull off early in the film. Things get complicated, of course, as Nicholson is pursued as a romantic partner by Braxton’s strong-willed daughter Jane, played by Kathleen Lloyd. All of this sounds very much like standard Western fare for the time, and was no doubt billed as such to audiences in 1976, but the movie thematically goes in a completely unique and different direction, to the delight of a viewer like me who generally despises predictability and shallowness of either story or character. There’s none of that here, folks.

The director Arthur Penn does masterful job here of laying down layer upon layer of commentary not only on the state of humanity but also on the bleak outlook on life in the Old West that most films in the genre never even try to address. Nicholson’s Tom Logan is one of the few smart individuals in the film by design, in a place where the absurdity of life and its invariably dismal events dominate everyone else.

McLiam’s Braxton is a cold unfeeling numbers man who loves law books, even as he subverts any real justice whatsoever time and time again. (The movie begins with a hanging that is brilliantly concealed from the audience right up until the moment it actually happens.) Logan’s compatriots have about as much competence as the Keystone Cops (which is why they’re poor and starving) and Penn plays this up constantly with a nihilistic bent reminding the audience that there is very little hope for anyone here. The train robbery scene is absolutely hilarious for it’s dark humor, a tool that is used constantly throughout the film. It’s like Blazing Saddles and High Plains Drifter had a love child and this was it.

But of course, it is the performances that make this movie so great. Brando was obviously unleashed entirely here, as his Robert Lee Clayton is flamboyant, brilliant, eccentric and insane all at the same time. Clayton is amorality personified, and yet his knowledge of human nature is always spot on, as Brando brilliantly allows the man’s bravado to slip at critical moments. The best of these is when, with a twinkle in his eye, he tells Braxton how confused he is how such a powerful man like himself could not keep a wife for any length of time.

While Brando is a force of nature here, it is Nicholson who is really meant to be the star, or at least the protagonist (even though Brando got top billing.) His character is the one with the arc, and it is amazing to see Nicholson take this man from failed thief and incompetent leader to nearly becoming an effective farmer by accident. The inserted love story humanizes Logan, and almost saves him, but of course, when Clayton begins summarily slaughtering Logan’s men one by one, Logan’s ultimate chance at redemption is lost.

My favorite scene is when Logan confronts Clayton in the bathtub, just after Logan becomes aware that Clayton has murdered one of his men, Little Tod played by a young Randy Quaid. Both men have spent the entire picture up to this point lying to each other about who they really are, and now that everything is revealed, the confrontation is intense. Clayton is unarmed and helpless, so they only thing he can do is turn away from Logan while in the tub, gambling he will not shoot him in the back. Brando sells it all so well, especially when Nicholson fires anyway, shooting a hole in the bathtub, and scaring both Clayton and the audience, who by this point have begun to question whether Logan is truly the good man we’ve been led to believe he can be. The movie of course answers that question by the end, but in yet another defiance of the genre, he is cleverly shown as being both good and evil at the same time. That’s nuance, folks, something most westerns at the time never bothered with showing.

You probably know I’m a huge Brando fan, and this movie shows him as middle aged but not yet inactive as he would eventually become, giving him the menacing edge necessary to still pull off such a larger-than-life character credibly. Believe it or not Brando himself actually designed the harpoon-like hand weapon Clayton uses here, giving some deadly bad-assery to a character that portrayed by anyone else could have come off as ridiculous.

All this, plus John William‘s amazing score (done just before Star Wars mind you) as well as some fantastic cinematography makes this one you have got to watch. Pay close attention, and prepare to have your expectations challenged, and I am certain you will enjoy it.

And of course, here’s the trailer for the movie to give you a bit of a flavor for it:

And although we did not discuss this movie itself, we did discuss the heck out of the Western genre in depth in Episode 57: